In high school, I stumbled upon the special community of blind people by chance. Through the recommendation of a friend of my mother, I volunteered at the China Braille Library, and my first task was to pick up two blind college students from a university for the blind. During my interactions with them, I noticed one of the blind individuals always carrying a portable device. Later, he told me that it could alert him of the distance between himself and obstacles. Before acquiring this device, he was hesitant to move around even indoors, but with this small device, his daily life had improved significantly. Realizing through my professional knowledge that it was simply an ultrasonic sensor, I was struck by how such a simple device could have such a profound impact on a blind person’s life. This inspired me to create a Braille learning machine.

As I continued my volunteer work, I discovered that mastering Chinese Braille was incredibly challenging, especially for blind children with congenital visual impairments. Chinese Braille has unique combinations for every sound, and the patterns for writing and erasing are mirror images of each other, making it especially difficult for beginners. Even with my sight, I struggled for a long time to write simple words in Braille, so I could only imagine how daunting it must be for those children. This led me to think that perhaps I could do something to assist these children in learning Braille, similar to the ultrasonic sensor. That very day, after consulting with some Braille experts at the library, I used my 3D printing skills to create a Braille learning machine over the next few weeks.

Since blind people lack vision, auditory and tactile senses are their primary sources of information. However, outside of school or the library, without the guidance of teachers, tactile sense becomes their only means of learning Braille. Therefore, I specifically added a voice module to my learning machine that could read out the content being written in Braille. This not only helped them memorize vocabulary but also facilitated self-correction of their Braille writing.

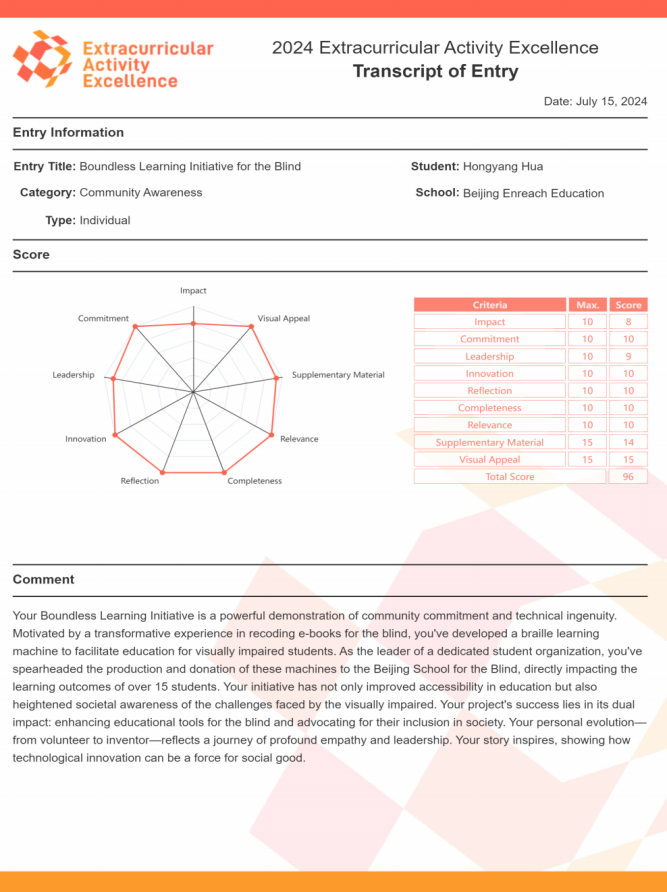

After assembling the learning machine, I nervously took my invention to the library. It turned out that my invention was useful and effective. Compared to tedious memorization, this little black box that could both practice and make sounds quickly gained the favor of many children and parents. On that day, I felt a different kind of pride for the first time. In the past, everything I did, including building Legos, was mostly to satisfy my own joy, but this time, through my invention, I brought light and fun to others’ lives, making me feel even better. It was also this success that gave me the confidence to do even better next time. The feeling of improving others’ lives with my own inventions excited me and inspired me to continue working hard to help others with my inventions. In the following days, I kept improving my learning machine based on their suggestions, such as reducing the distance between each point and enriching the voice combinations. Now, I have made nearly 20 learning machines, which are used in classrooms at blind schools in Beijing. I hope that in the future, I can acquire more knowledge and improve more people’s lives, not just those of the blind or myself.

The following picture shows me participating in volunteer service.

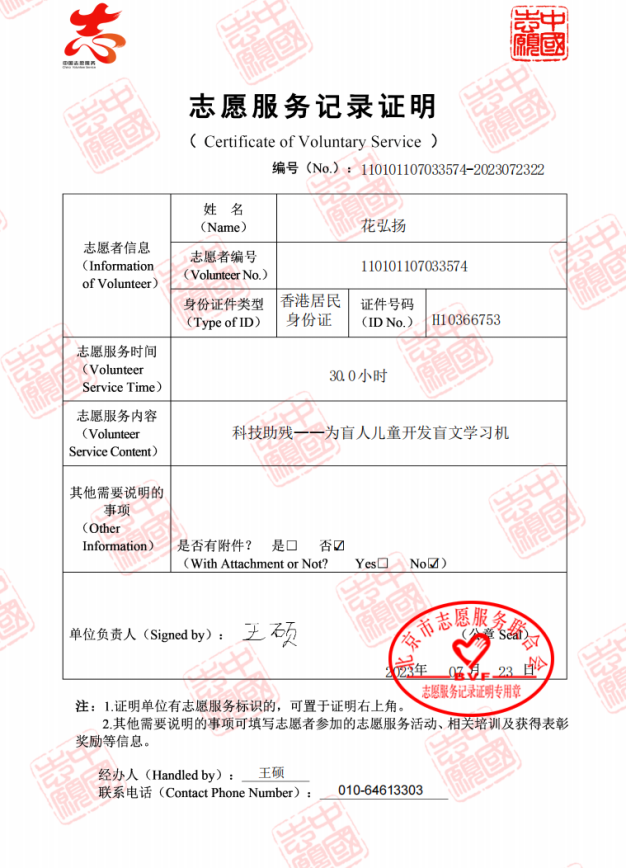

The picture below is a certificate from my volunteer service.

Certificate of voluntary service

In addition to this invention, I have also worked on proofreading electronic books for the blind.

In every corner of our cities, there are people who communicate with the world in their own unique and resilient way. They are the visually impaired – a large, yet often overlooked segment of society. In today’s world, where a mere tap on a screen can open vast oceans of information, these individuals navigate the frontiers of knowledge with their fingers and ears, facing significant challenges. Despite the availability of screen reading technology, accessing electronic books remains a formidable obstacle, particularly when it comes to specialized or newly released titles. The digital resources available are still insufficient to meet the diverse reading needs of the visually impaired.

As individuals blessed with sight, it’s hard for us to truly understand what it’s like to live as a visually impaired person – to comprehend how they read, the daily challenges they encounter, and what our commonplace experiences mean to them. I am driven by a hope that my work can bring some light into their lives.

Moreover, I have engaged in the restoration of cultural relics. This field demands unwavering persistence and intense concentration. Previously, when I thought of artifact restoration, items like porcelain and clocks came to mind. However, restoring artifacts such as these showcases the evolution of human craftsmanship, while the restoration of ancient books and paintings highlights the development of our cultural and intellectual heritage. Observing an authentic piece hanging on the wall, the aged and fragile paper breathes the passage of time. Looking closely, I can discern the varying intensities of ink that have bridged centuries. It’s almost as though the script was penned yesterday, and I am standing right next to the author, scrutinizing each stroke crafted hundreds of years ago.

My commitment to the restoration of cultural relics stems not only from the opportunity it affords me to journey through historical epochs and to personally touch those treasures that time has forgotten, but also from the profound sense of mission and responsibility it imbues in me, making me a bridge linking the past to the future. Each artifact, be it a finely crafted piece of porcelain, an intricately designed clock, or an ancient book or painting steeped in cultural depth, is a testament to the crystallization of human intellect and emotion, and a conduit for the memory and cultural legacy of a civilization.

The restoration of ancient books and paintings goes beyond merely reviving their luster. It is an act of perpetuating and enhancing a cultural ethos. These works, silent yet eloquent like poets of yore, employ brush and ink to narrate stories spanning millennia, capturing the transformations of epochs, and reflecting the intellectual and emotional depths, and the aesthetic aspirations of the ancients. Through our restoration efforts, we not only reconstruct their physical form but also unearth and illuminate the cultural significance underlying these artifacts, enabling future generations to behold the true visage of history and to experience the allure and warmth of our shared cultural heritage.